From the Archives: Notes on scientism

How the worship of science rotted Western culture and the modern mind

This essay was published originally in December 2022, when I had been writing on Substack for only a few months to a tiny handful of subscribers. I believe my earlier work will be of interest to many of my newer subscribers who have not read it, and plan to occasionally re-publish these older essays that cover general themes, updating and editing them slightly for the present times.

Thank you again for subscribing. Please do share my work with those you think may appreciate it.

I will be publishing more essays on politics and culture, as well as book reviews and recommendations, over the coming weeks and months.

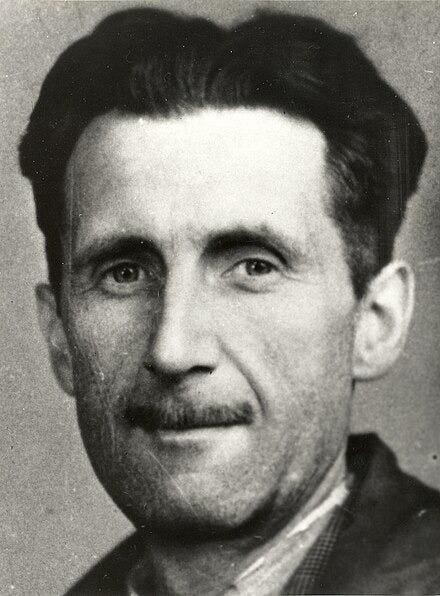

“I saw in an American magazine the statement that a number of British and American physicists refused from the start to do research on the atomic bomb, well knowing what use would be made of it. Here you have a group of sane men in the middle of a world of lunatics. And though no names were published, I think it would be a safe guess that all of them were people with some kind of general cultural background, some acquaintance with history or literature or the arts — in short, people whose interests were not, in the current sense of the word, purely scientific.” — George Orwell, What is Science? (1945)

The rise of scientism is one of the darkest developments of the last century. Indeed, it is the development that has enabled the broader dismantlement of Western civilisation. The scientific ideal has come to be regarded as a prime intellectual and moral virtue. Indeed, the Academy has been ingrained with this deep bias for decades. The so-called “social sciences” have now largely replaced the traditional arts. Pseudoscientific “lenses” — the simplistic and spurious formulae of Marxism and feminism, for example — are overlaid on the world as if they are natural laws by which humans and their cultures will necessarily abide.

The reign of this scientific zeitgeist has not only poisoned the realm of culture and the arts — it has usurped them entirely and now sits enthroned in their stead. Disciplines once devoted to the highest ideas in philosophy and literature are now cold wastelands of politicised absolutes and dogmatic “-isms”. Pseudoscience has wrapped itself around the entire Academy, and hence the whole of Western culture, for it is from the Academy that our civilisation takes its moral and intellectual lead.

An education comprised of science in the absence of culture or traditional book-learning is like a tree without leaves: it is missing its richest, most beautiful and most vital aspect.

The consequence of science’s intellectual dominance has been its political takeover. It is accepted, indeed expected, that elected rulers will do whatever the scientific experts tell them to. Equally dangerously, such experts are often chosen selectively to support exclusive political outcomes — from weapons inspectors, to climatologists, to epidemiologists. Their pronouncements are used as political justifications. In the post-Enlightenment age, the scientist has thus assumed the role of the high priest.

In his 1945 article What is Science?, George Orwell captured the spirit of this new widespread deference to the scientist: “The world [many people think] would be a better place if the scientists were in control of it.” The Nazis’ crimes, he notes, were actively enabled by highly placed scientists, many of whom “swallowed the monstrosity of ‘racial science’”, which was a scientific and cultural orthodoxy of the time, not just in Germany but across the West.

Orwell decried the replacement of the traditional humanities (philosophy, history, literature and so forth) with science. Science’s sole remit is the inquiry into the natural world. Its advancements have nothing to tell us about ethics, nor aesthetics, nor metaphysics, nor any of the political considerations that follow from them. In other words, it contains within it no philosophical or moral meaning. Science is an intellectual tool — but one that carries before it the potential for immense material, and thus political, power. It is the responsibility of culture and philosophy to provide the higher guardianship of that power: to constrain and channel it in accordance with virtue and good sense.

Importantly, Orwell also observed that scientific education, devoid of real cultural learning, actively limits and impoverishes the Western mind. He wrote:

“Its probable effect on the average human being would be to narrow the range of his thoughts and make him more than ever contemptuous of such knowledge as he did not possess: and his political reactions would probably be somewhat less intelligent than those of an illiterate peasant who retained a few historical memories and a fairly sound aesthetic sense . . . At the moment, science is on the upgrade, and so we hear, quite rightly, the claim that the masses should be scientifically educated: we do not hear, as we ought, the counter-claim that the scientists themselves would benefit by a little education [my italics].”

This point is far more obviously true now than it was in 1945. The scientistic mindset has bred an obnoxious, ignorant certitude into our culture. Every matter of political and cultural importance is now treated with dogmatic, clinical assuredness, from Covid policies, to the Ukraine conflict, to global economics, to the prominent leftwing cultural attacks. A single dominant critique takes hold — frequently underpinned by bogus science, or at least some bogus, half-educated interpretation of events — and all scepticism is treated with contempt by default, precisely because it is sceptical.

The scientific lens, that of absolute laws and implacable causation, has been projected onto the world of politics and culture. As Orwell observed, the excessively scientific education of the modern mind has “narrowed the range” of its thoughts, making it the slave to mechanistic, uniform, mass-conformist thought. Deprived of any profound education in the arts — in philosophy, literature and the classics — the intellect is captured easily by hubristic pseudoscientific assertions that are essentially always political in their nature.

The greatest philosopher of the twentieth century, Ludwig Wittgenstein, was another great prophet of the scientistic threat. In Culture and Value (c. 1945), he wrote:

“People nowadays think that scientists exist to instruct them, poets, musicians, etc. to give them pleasure. The idea that these have something to teach them — that does not occur to them.”

The humanities, derided and neglected for nearly a century, have now fallen in Western civilisation. The classic texts of Homer and Virgil, once compulsory in school, are now barely read. The “dead languages” of Latin and Greek that for so long provided the indispensable portal to the roots of Western culture are widely disparaged as useless. Poetry and philosophy are treated as trivial articles of recreation, rather than foundational pillars of learning without which no mind can hope to be educated and no society can hope to flourish.

Education used to be almost synonymous with the arts. As the arts have become vacuous, vast portions of the modern intellect have concomitantly lost all vitality. The mind is now governed instead by the linear and narrow methodology of the scientist. Thus Wittgenstein wrote that “science is a way of sending [a mind] to sleep.” Scientific learning, in isolation from the richness of a cultural education, not only rots important faculties of a mind, but trains what is left of that mind to see the world and everything in it through the mechanistic rubric of causality and use.

The point is not that science is bad: it is of course, in its proper place, an important civilisational good. The point is that an education comprised of science in the absence of culture or traditional book-learning is like a tree without leaves: it is missing its richest, most beautiful and most vital aspect, and has lost the very essence of itself. Indeed, it has lost its purpose.

It is in the barrenness of scientism that we see its connection to political despotism most clearly. The twentieth century transmogrified science from a mere intellectual tool into a sacred moral observance. As the British philosopher Roger Scruton remarked, the error lies in the modern expectation that science will “pass from an explanation of something to the meaning of something.” The theory of evolution, for example, is treated not merely as an explanation for genetic variations within species: it now supposedly accounts for the very meaning (or rather meaninglessness) of life, usurping religious traditions. Cosmology, too, plays an important role in driving the new atheistic worldview. Moreover, the claims of some climate scientists give a kind of messianic purpose to the lives of thousands of political activists. And the very creation of some new technology is regarded as a reason to use it.

Science has thus subsumed and reformed the traditional theology, morality and metaphysics that once guided Western cultural life.

This is the true heart of scientism in the modern world: it fills the philosophical and moral void that was left by the decline of Western Christianity. Science, often framed more broadly as “reason”, has been sublimated beyond its proper limits, and remoulded into a surrogate outlet for the intellect, the morality and the spirituality of modern Western man.

Indeed, it is through this outlet that the darkest aspect of scientism has emerged to the fore — its use as an instrument of political control. Scruton observed:

“Scientism is really a king of magic. . . It involves using science to conjure things, to reassemble human life in order to exert a sort of control over it.”

In the despotic states of the last century, science was engineered in reverse to fit some anti-human political end-state. To keep favour with the prevailing ideology of Nazi Germany, scientists avowed and developed racial Darwinism. In Stalinist Russia, state dogma was underpinned by pseudoscientific geneticists, who claimed that parents pass socially-acquired characteristics on to their children. The new Soviet man and woman could therefore be created, it was claimed, by people embracing desirable traits which could then be passed on to their offspring. Dissenting scientists were exiled, imprisoned or executed.

Indeed, one of the most important scenes in Orwell’s Animal Farm is that of the pigs’ initial theft from their fellow animals following the revolution. Having liberated themselves from human control, the animals are perturbed at the pigs stealing milk and apples from the communal stores. Squealer, the pigs’ advocate-in-chief, explains the act:

“Comrades!” he cried. “You do not imagine, I hope, that we pigs are doing this in a spirit of selfishness and privilege? Many of us actually dislike milk and apples. Milk and apples (this has been proved by Science, comrades) contain substances absolutely necessary to the well-being of a pig.

Orwell understood the reliance of the despot upon science as an instrument of control — a dark art of conjuring and deception. In Modernity, the scientist acts as both master and servant. He marks out new philosophical territory in the culture and defines future political ends. Yet he also serves the powerful in the role of an advocate and inquisitor, convincing the sceptical to acquiesce against their better senses, and defeating scientific opponents with venomous slurs (“denier”, etc.) designed to intimidate and exile. In Modernity, graphs and statistics are not only political instruments, but weapons of coercion and dogmatic enforcement.

What is the remedy to scientism? It lies in the conscious rebuilding of the West’s foundation in the arts. Orwell wagered that the scientists who doubted the wisdom of the atomic project would be those possessing “some acquaintance with history or literature or the arts.” He was surely right. It is this learning which fundamentally civilises us — which roots us in the soil of our tradition, our morality, and to each other. True education resides in the classics, literature and philosophy, on top of which the hard sciences stand as a single pillar.

Scruton told us that one of the foremost duties of the arts lies in helping us to recognise fakery from the genuine article — not only in a work of art, but also in the quality of an idea. Only through the arts can we learn to differentiate wisdom from folly, truth from deception, culture from pseudoscience, and good from evil. It is thus only through our cultural heritage that scientism can be dethroned and our civilisation regrown.

Thoughtful and incisive.

I like this article very much, thank you.

I would go further and observe that science as a way of thinking must be subject to the Logos, that is the Word of God in the Person of Jesus Christ. The very earliest scientific thinkers were convinced of this (Francis Bacon and the Novum Organum, for example). This connection is now forgotten - the celebrity christian scientists (like Francis Collins) are clueless about it and have pursued research that is both dangerous and junk.

Once science is adrift from the Logos, then it has neither purpose nor ethical constraint and the the outworking results in junk science or dangerous science. I wrote a substack article on "Science and the Mystery of Lawlessness" which begins to explore this.

So the remedy is not liberal arts per se, but rather a repentance that brings our science back into alignment with the Logos. Eschatologically, this is unlikely.