On cultural Marxism: the ghost of Antonio Gramsci

How the insurgency of critical theory seized long-term power for the left

“You probe with bayonets: if you find mush, you push. If you find steel, you withdraw.” ― Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

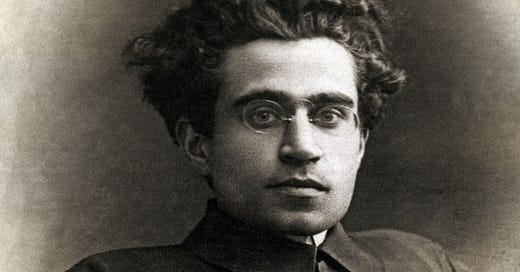

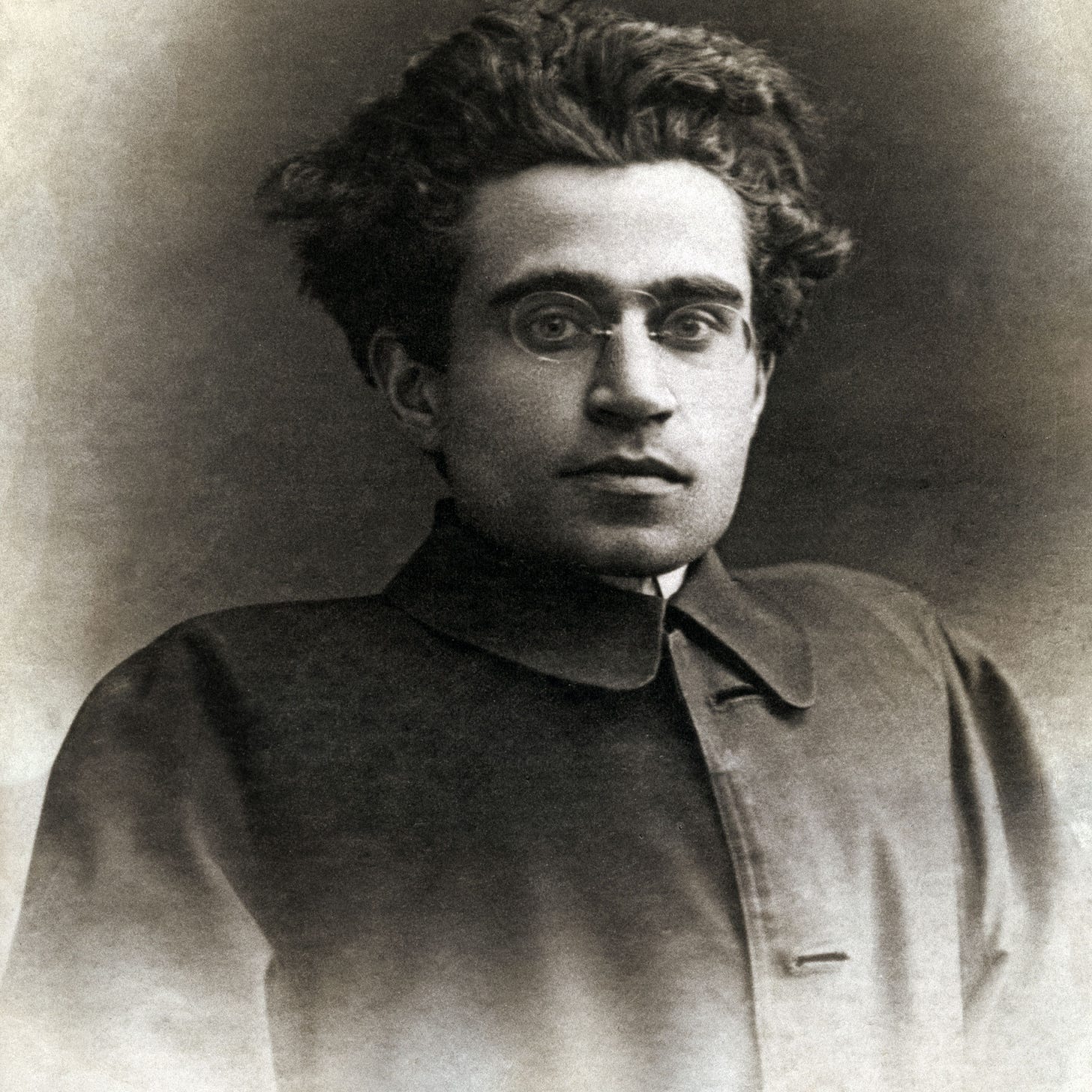

It was from a prison cell in the Italian city of Bari that the stratagem for the left’s control over the West was authored. Antonio Gramsci, former leader of the Communist Party of Italy, was arrested in 1926 for his visceral opposition to Benito Mussolini. He remained imprisoned until dying in 1937 from the privations of his conditions. A talented intellectual and a tireless activist, Gramsci wrote thirty notebooks and over 3,000 pages of historical polemics from his cell. Through the deep influence of these works on the Marxist tradition, he became the architect-in-chief of the doctrines that have enthroned the left in its current position of supreme cultural and political command in the West.

Gramsci created the modern archetype of the activist-revolutionary — the individual agitator who evangelises relentlessly on behalf of the Marxist cause. This marked an important departure from the origins of Marxist theory. In The Communist Manifesto (1948) and Das Kapital (1867), Marx argued that history proceeds via “dialectical materialism”: the continual conflict of opposing material forces in society. It is through an ongoing “dialectic”, or social battle, between classes that change is enacted. Economic conditions are, according to Marx, the principal cause of all historical change. Once the materially oppressed classes become “conscious” of their exploitation and demand liberty and equality, a revolution against their oppressors is fought.

Thus, argued Marx, the peasantry revolted against feudalism, ushering in a period of mercantilism. Mercantilism, in turn, gave way in time to the capitalist order in which the industrial and agricultural workers live in direct material juxtaposition to their oppressors — the “bourgeois” class that owns the means of production. The essence and allure of Marx’s theory lies in his claim that it is a matter of historical — indeed, scientific — inevitability that the workers will one day gain a collective class-consciousness and revolt across the industrialised world to create a communist utopia of perfect equality and fraternity. For the Marxist, this theoretical end-state for human society is not only perfectly rational, but is determined by anthropological laws.

“The mind of the child is an important object of revolutionary propaganda — a blank slate from which the old cultural norms can be easily banished and onto which new ideas can be inscribed without resistance.”

Yet, exactly half a century after the publication of Das Kapital, the acolytes of Marx had become impatient for the revolution. That lauded proletarian consciousness did not appear to be forthcoming. If the workers would not awaken themselves, then a class of enlightened revolutionary seers would need to wake them up. It was this demand for decisive, even violent, action, or “praxis”, that defined the strategy of Vladimir Lenin, who led the Russian Revolution of October 1917 that midwifed the Soviet state. Whilst in exile in Switzerland during the Great War, Lenin developed the doctrine of “vanguardism”, according to which a rapid coup would seize power and emancipate the proletariat. In one of history’s most critical turns, in April 1917 Imperial Germany — eager to destabilise and disrupt Imperial Russia on its eastern flank — provided Lenin and his cohort with safe passage into the heart of Russia in a diplomatically sealed train. And so a new nightmare of stunning and unprecedented violence, famine, strife, and terror was birthed in the new Soviet Russia.

By the early 1930s, the acute human toll from the first of Stalin’s five-year-plans was evident. And by the time of Gramsci’s death in 1937, Stalin had reached the apotheosis of his paranoia, the Great Terror, in which 700,000 officials, dissidents and military officers were murdered. The transparent deterioration of the Soviet utopia forced a crisis upon the Marxists of Western Europe: the theory in practice seemed to create hell, not utopia. In response, Gramsci refined a new theory of Marxist critique, attempting to both avoid the bloodshed of the Soviet model, and also to account for the cultural complexities of European democracies. From Lenin, he took the doctrine of praxis. Lenin was right: the revolution was not a self-fulfilling inevitability — it could be enacted, thought Gramsci, only via the agitations of the intellectually and morally enlightened. But whereas Lenin had viewed praxis through the prism of decisive, narrow action by a glorious few against the society’s centres of power, Gramsci explained that widespread cultural groundwork had to be laid prior to any political takeover. For the revolution to gain traction, Marxist theory — the utopian vision — had to be inculcated in the minds of the oppressed for years, even decades, in advance.

Gramsci was invoking a distinction in contemporary Italian political thought between “force” and “consent” — the idea of political authority in democracies relying ultimately upon widespread public cultural support. Power in Western nations, Gramsci observed, is enmeshed intimately with the broader “sturdy structure of civil society”: universities, schools, churches, public intellectual bodies, the press, and so forth. It is through these institutions that the ideological consent of the people is cultivated — specifically via the reassurance and advocacy of teachers, priests, journalists, and prominent public intellectuals. Such cultural leaders both consolidate and personify the dominant cultural narratives. It is in this way that political authority pacifies dissent and moulds opinion in favour of its political ends.

Power, Gramsci argued, is therefore exercised principally through “cultural hegemony”. In Ancient Greece, the hegemon was the dominant military state whose will was held in precedence among the surrounding polities. Yet it was through cultural, rather than military, dominance that Gramsci saw the true heartbeat of Western political power. Capturing the cultural institutions is, by Gramsci’s lights, the same thing as capturing the society itself. Far from aiming for the shocking coup of Lenin, the revolution ought instead to proceed as a silent, many-tentacled undercurrent that ingrains itself gradually in the fabric of the culture.

Importantly, Gramsci — like all leftists — was an anti-realist about human nature. He believed that historical conditions, not the innate nature of man himself, creates culture. He wrote: “Man is above all else mind, consciousness — that is, he is a product of history, not of nature [my emphasis].” Tellingly, Gramsci repeatedly attacked the idea of common sense, which he argued was merely a collection of incidental taboos and cultural practices that had become embedded as a kind of quasi-logic in the minds of the people. For example, for Gramsci there is nothing natural, nor even rational, about men and women rearing children together in the family unit. It is simply a product of history and circumstance. The culture is thus not a fixed entity that obeys the innate laws of human nature, as per Aristotle. Rather, it is something endlessly shifting and malleable. It is here that the most profound confusions, and the deepest dangers, of Marxist theory exist. Such “critical theories”, which seek to ceaselessly dismantle organic culture, have haunted the West for over a century, deracinating it from the roots of tradition.

In his Prison Notebooks, Gramsci contended that it is the job of the revolution’s intellectual high priests to refine and advance the rich theory left by Marx. Moreover, the duty of the intellectual lies in unpicking and rebuilding the people’s understanding of common sense — “renovating and making ‘critical’ an already existing activity.” So successful has this approach been that the critical theories of the neo-Marxists are today household ideas. Their language and arguments are familiar to almost everyone. As Gramsci demanded, the critical theorists dismantle every pillar of Western culture — its traditions; its interpersonal relations; its purported power structures — and identify the oppressors that have lain hidden in the shadows for centuries. It is through the discourses of critical theory that political “consciousness” among social groups is raised, and new civic enemies can be synthesised from the ashes. The critical theory seeks to dismantle in order to rebuild for its own political ends. The ongoing problem for Marxists, however, is that the dialectical battle within society for which they yearn does not emerge by itself. It can only be generated via tireless agitation.

Yet, the genius of Gramsci’s strategy lay in his recognition that this “consciousness-raising”, which would lead eventually to the dialectical battle between the oppressed and their oppressors, could be sown successfully only in fertile cultural ground. He thus advocated for a two-step strategy to revolution. First would come the war of position. Once achieved, this would be followed by the war of manoeuvre. The war of position would slyly emplace Marxist critical theorists in all of society’s core institutions. Humanities departments of major universities would need Marxists on the inside, as would the major media outlets, and all of the schools. Indeed, as we see now, the primary school is in many ways the central battleground within which cultural worldviews compete for hegemony. So it is in modern China; and so it was in Soviet Russia. The mind of the child is an important object of revolutionary propaganda — a blank slate from which the old cultural norms can be easily banished and onto which new ideas can be inscribed without resistance.

The localised, widespread nature of the war of position is paramount. It proceeds gradually and silently, with populations accruing tolerance to Marxist theory over decades. Like all leftwing intellectuals, Gramsci knew that religion, particularly European Christianity, is the natural enemy of the utopian project. The belief in divine meaning and justice engendered by religious worship provides a deeper portal through which the hopes and cultural mores of humanity are channelled. Moreover, religion inculcates an innate scepticism towards even the theoretical possibility of attaining earthly paradise. Thus Gramsci wrote: “Socialism is precisely the religion that must overwhelm Christianity.” The defeat of Christianity was perhaps the lynchpin in Gramsci’s scheme, as it had been for the Bolsheviks in Russia and for the Jacobins in Revolutionary France. Except, instead of violence and intimidation, the weapon of choice was the sly and steady cultural takeover of the Church from the inside.

Allied to this was Gramsci’s attack on the family. Marriage, he argued, is a pernicious social mechanism through which the attitudes and mores of the dominant culture are personified and — importantly — transmitted to children, thereby propelling hegemony through the generations. Indeed, the family is oppressive in its own right through its exploitation of women and children, and hence is the natural social progenitor of fascism. We therefore see on Gramsci’s model a two-pronged assault on the mind of the child: first, the attempted dissolution of the familial bonds that foster traditional moral and cultural education; and, second, the cleaving of the child to the state via its schools, which he insists must be infiltrated and eventually led by the critical theorists. The parents simply create the child. The state, which in time will become a Marxist hegemon, must command the nurturing of the child.

“Critical theory, a de facto intellectual attack on the West from within, swelled through the universities in the twentieth century, subsuming nearly every discipline and applying increasingly drastic critiques to every inch of the culture.”

Likewise, popular culture — a crucial means by which the dominant ideological mores are purveyed — must gradually be captured, transforming the culture’s core motifs into Marxist propaganda. Novels, popular music, films and magazines must become mouthpieces for critical theory. The genius of the Gramscian strategem, and the reason for its long-term success, lies in its gradualism. The agitation works steadily, building a tolerance to Marxist theory that could never be achieved in a single outpouring of revolutionary fervour. Indeed, it is predicated in large part on having enough critical theorists in positions of authority — as teachers, priests, government officials, and so on — that confidence in the movement becomes the default presumption.

Gramsci’s theory is redolent of Lenin’s notorious remark on the nature of enacting revolutions against the instincts of the masses: “You probe with bayonets: if you find mush, you push. If you find steel, you withdraw.” But whereas Lenin was referring to the direct use of force and coercion against those bound to tradition, Gramsci applied this same precept to the steady machinations of a cultural takeover. Where the critical theorist finds fierce resistance, he must withdraw — for now. And where he finds compliance and complacency, he must proceed. By carefully testing and calibrating the various pressure gauges of the overall culture in this way, the Marxists have been able to march implacably to the centre of Western civilisation.

With the war of position won, and the cultural conditions set, the Gramscian strategy calls next for the war of manoeuvre: the open agitation, even potential literal warfare, against the remnants of anti-Marxist Western tradition. The keystone to this is the raising of consciousness among multifarious “subaltern” groups — distinct oppressed and exploited classes whose experiences have been “marginalised” in the dominant culture. In his Prison Notebooks, Gramsci identifies slaves, peasants, various religious groups, different races, the proletariat, and women as constituting subaltern groups. Importantly, Gramsci does not discuss the concept of the subaltern in the singular: rather, it codifies a broad web of disparate groups which, if agitated together cleverly, might unite in common cause — in “solidarity” — against the dominant culture. This was an important departure from the discourses of Marx and Lenin, which viewed the proletariat as the single focal point of specifically material oppression in the ongoing dialectic of history. Instead, argued Gramsci, a united front must be mobilised from across a plethora of groups, thereby providing the revolution with cultural depth and numerical superiority.

Critical theory is the means by which that consciousness is raised. The duty of the Marxist intellectual is, according to Gramsci, to illuminate the oppressions experienced by marginalised peoples — whether they realise they are oppressed or not. To succeed, the critical attack must account for the plurality of Western culture, probing into every corner of human difference in order to dismantle — and subsequently reconfigure — social attitudes. The real work of this project was undertaken throughout the twentieth century by the Frankfurt School, over which Gramsci had an immense influence. The Frankfurt School was an inter-disciplinary group of Marxist theorists in interwar Germany. Forced to relocate to the United States in the 1930s, the School’s thinkers became permanently embedded in the country’s major universities. Through its original thinkers such as Marcuse, Horkheimer and Adorno, a raft of “critical lenses” were applied to Western history, individual and collective psychology, racial relations, sexual practices, the family, popular culture, and power itself. This movement, a de facto intellectual attack on the West from within, swelled through the universities in the twentieth century, subsuming nearly every discipline and applying increasingly drastic critiques to every inch of the culture. The Frankfurt School marked the inception of the acadamic-cum-activist with whom we have become all too familiar.

The feminists who agitated for the Sexual Revolution of the 1960s, and Michel Foucault, whose poisonous critical theories of power hold such sway today, were the direct intellectual descendants of the Frankfurt School. They were part of the same movement. So, too, are the intersectional feminists and critical race theorists that have authored the woke movement. The success of this intellectual lineage illustrates the Marxists’ adherence to one of Gramsci’s chief precepts: “Since defeat in the Struggle must always be envisaged, the preparation of one's own successors is as important as what one does for victory.” The Gramscian revolution is, above all, generational — it is not a moment, but an epoch of ever-thickening cultural, and hence political, dominance.

This is precisely what has happened within the Western Academy. Steadily at first, but now rampantly, the left has cultivated its hegemony within universities, winning the war of position. As the historian Niall Ferguson has observed, leftist syndicates grew surreptitiously within departments over decades, increasingly filling prominent professorships with fellow Marxists. For example, when the great conservative historian Richard Pipes left Harvard in 1996, he was replaced not with another eminent conservative, but with a leftist. This is not simply group-think or bias at work. It is in fact doctrinal to the neo-leftism of Gramsci and the Frankfurt School that Marxist “allies” should be elevated to positions of prominence, whilst opponents should be regarded as political enemies and thus suppressed where possible in order to limit the influence of traditionalist thought. Exactly as Gramsci prescribed, it is through the intellectuals that education itself can be moulded in the image of the revolution.

It is through the Academy that the ideas of the movement have transformed into their current moulds. And it is within the Academy that literally millions of impressionable young adults have been successfully agitated into crypto-activism for cultural Marxism. The arts at all major universities are now taught principally through the critical lenses of the Frankfurt School and its intellectual successors. Hence inevitably — and precisely as intended — every institutional organ of Western civilisation has now been infiltrated by the ideology, from the judiciary, to schools, to churches, to corporate boardrooms, to the military, to the highest reaches of elected government.

Kindergartens in the United States are haunted by the spectre of Drag Queen Story Hour: ghoulish men dressed as female prostitutes, relentlessly lecturing small children on the breakdown of the traditional family. In Scotland, people are charged with “hate crime” for stating inconvenient facts on Twitter. In every institution, the doctrine of “diversity and inclusion” now sits enthroned as the reigning orthodoxy, overshadowing the precept of merit. In many Western nations, the dogmas of the cultural Marxists now sit under the direct protections of the law. Indeed, the very notion of the common law is under constant erosion from the selective application of subjective concepts such as “hatred”, which are used only in protection of the woke movement’s quasi-victims. In aesthetics, the critical theorists have plumbed new depths, attempting to turn vulgarity into beauty and denigrating true beauty wherever it is found. A new “wave” of feminism seeks as its core motif the deliberate emasculation and demoralisation of Western men. All of this originates in the Academy. It is the direct inheritance of Gramsci and the Frankfurt School.

Grasmcian strategy has provided the manual for the progressive movement, as it did for the long march through the institutions that galvanised Maoism in post-revolutionary China. And the twisted logic of the West’s cultural Marxists has plenty left in it yet. It is obvious to anybody that Western culture is deteriorating exponentially. Yet, it is perhaps in Lenin’s analogy of the bayonet that we might find an important moral by which the dominance of the Marxists can be dispelled. Lenin told his acolytes to drive forward where they found mush and to give way when met with steel. The metaphor unwittingly captures the opportunistic cowardice on which all Marxist agitation is essentially based. It is ultimately through unremitting honesty and defiance that the ravages of propaganda are defeated. And it is only from within the walls of human courage that everything sacred and vital to Western culture can be protected.