Some recommended reading: a shortlist of forty books

A concise reading list of great Western works

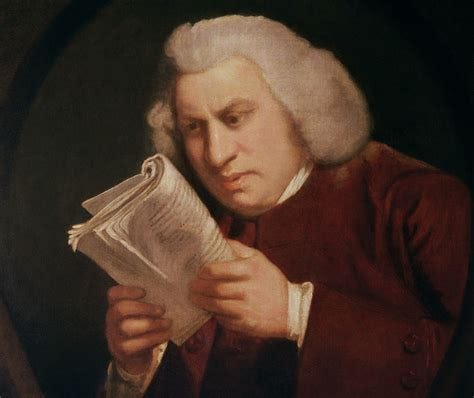

"The greatest part of a writer's time is spent in reading, in order to write: a man will turn over half a library to make one book." — Samuel Johnson (1709 — 1784)

"It’s the hard books that count. Raking is easy, but all you get is leaves; digging is hard, but you might find diamonds.” — Mortimer J. Adler (1902 — 2001). Adler was a great American educator, philosopher and theologian.

Introduction

What we read matters immensely. For it is through literature, above all else, that the intellectual and moral essence of our civilisation is imparted in its purest form. Only in books are we able to engage so carefully, and so deeply, with the greatest minds of our culture.

As well as observing that it's the hard books which truly count, Mortimer Adler also noted that television, radio and other fleeting sources of entertainment are merely "artificial props": they give the illusion of stimulation whilst depriving our minds of the intellectual, moral and spiritual resources needed to grow. Television, social media and so forth numb our faculties, leaving us susceptible to the whims, contradictions and propaganda of the modern era.

Indeed, this is now also true of many books that we are encouraged to read. The airport fiction and motivational business books of mass acclaim deal exclusively in the motifs and ideas of now. They are specific, not universal; and they are easy, not hard. These books offer only the pretence of stimulation, insight and profundity. Nobody will read them in five years' time and readers will remember almost nothing of their contents.

This is of course not to say that all of our reading must be difficult. An Agatha Christie novel, or an adventure tale by Alexandre Dumas, is an important source of enjoyment and stimulation. But it is to say that not all reading is equal in worth. The great books are inimitable. They confer wisdom, truth, and knowledge, and illuminate the most brilliant insights and the deepest questions of human thought. Moreover, they imbue us with high standards of written style and rhetorical expression. The more we read, the more adept we become at grappling with difficult ideas and complex language, and also connecting insights in a wide internal network of learning that we have accrued.

As the American philosopher Edward Feser remarked recently: "Regular, patient, sustained engagement with serious essays and books — not tweets, not podcasts and videos, not articles of the ephemeral kind, but essays and books carefully thought through and crafted to have a long shelf-life — is necessary for developing a serious mind."

The Western canon thus provides a kind of intellectual and moral armour: the great books not only offer consolation through life, but also elevate one's capacity to think, to express oneself, and so to lead others.

Hence, many of history's great men were rigorously self-educated in the Western canon. Napoleon Bonaparte and Winston Churchill both embarked on highly ambitious reading projects as young men, outside of their formal educations. As an adolescent, Abraham Lincoln walked for miles each day to a public library, engrossing himself in the great books for hours on end, before returning to his impoverished family home.

As well as being great men of action, all three had accrued an extraordinary understanding of history and literature, and were thus able to comprehend their times with a clarity and acuity that eluded their contemporaries. Moreover, they were able to defeat their dialectical opponents, and inspire and lead their allies. Reading had steeled their intellects, and given them an extraordinary intellectual vigour and power of prophecy.

We therefore see that, as physical training is to the body, deep reading is the fire that transforms the mind from mere metal into a sword.

Yet it has become difficult to know where to begin with the great books. Modern education focuses largely on the recent classics, without grounding pupils in the great sweep of our literary inheritance from Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Moreover, there is a malicious and benighted “woke-washing” of the Western canon at work in our universities and schools, which is banishing many vital works whilst warping the true meaning of those that are taught.

Likewise, most modern publicly available classic reading lists are weighted disproportionately to twentieth century writing that has not yet truly stood the test of time. Such lists rarely expose the reader to the full span of Western literature, from Antiquity through the Mediaeval era, and into the Modern age.

As a teenager in the 2000s, I wanted to read the great books, but discovered them only in a piecemeal fashion, based on individual recommendations or online reviews. What I wanted was a consolidated shortlist of books that would bring me into the fold of the Western canon within a relatively short period of time; and I suspected (rightly, I eventually learned) that the popular reading lists were withholding the true depth and quality of the canon.

I have thus compiled below a list of forty books that I would now set my teenaged self before beginning university. The purpose of the list is to give an overview of the Western canon, from its origins in Antiquity up to the modern day. It includes the verse, novels and essays that have comprised the central pillars of Western learning and culture.

This is a shortlist of books that I would recommend to a young person who is, for example, planning to study a humanities course at university. Indeed, I believe this will put them streets ahead of their peers, whether they are studying English, Classics, History, Philosophy, or Law.

Moreover, this list can be used as a guide by anybody that wants to deepen his or her reading in the foundational works of our civilisation. A dedicated reader with an otherwise busy life could comfortably read these works within two years (indeed, far less time, since some of the books can be read in a single day).

Naturally, a list of this brevity has limitations. It is not intended to list the forty greatest books ever written. Rather, it is meant to showcase a grand sweep of the canon, offering variety in form, style and content along the way. There are classics of Antiquity, Russian greats, Renaissance essays, Victorian classics, the works of Samuel Johnson, modern history, and brutal military memoir. The list is of course, to some degree, a reflection of my own tastes and my own reading, which is itself a work in progress. However, the list is comprised of objectively exceptional literature, much of which has been the mainstay of traditional university reading lists for decades, even centuries in some cases.

I have offered a brief description of each work, and suggested further reading where applicable. This is somewhat cheating against the notion of a forty-title shortlist, but the intention is that the headline works stand as gateways to yet deeper reading.

There are many gaps in the list. Jane Austen, for example, is not given a place. Nor are Chaucer, George Eliott, Edgar Allan Poe, and Thakeray, to name but a few. These writers are of great importance and should be read. But the list is deliberately limited and inexhaustive, and I have tried to choose some writers and works that deserve to be better known. I intend in time to add further titles beneath the shortlist in sub-categories — classic crime; history; military works; poetry, etc. — so that it becomes an ever-developing resource.

I will cheat one final time: adjacent to the list, I recommend buying the following three works as lifelong reading resources.

The Bible. This is the foundation of our civilisation, our morality and our culture. As Orwell observed in his own day, basic familiarity with the core stories of the Bible, even among educated people, is quickly vanishing. The Bible is the literary, intellectual and moral centrepiece of the Western world, and must be read deeply and widely.

An anthology of English literature. I recommend the Norton anthologies. I had to buy these for a university course and still read routinely from them. They contain entire works, such as Beowulf, as well as short novels and vast amounts of poetry. Not only do these anthologies hold great individual works, they also illustrate the grand chronology of English writing over millennia, from the very inception of the nation.

An anthology of English verse. I recommend the Oxford Book of English Verse. The reading of poetry is disappearing rapidly. Yet, it is in verse that many of the West's greatest ideas have been expressed. It is in the works of Shakespeare, Dryden, Wordsworth, Tennyson and T. S. Eliot that we are perhaps most moved. These are the highest expressions of our language, which stay with us long after reading. Children used to be made to memorise verse in school. Not only was this to familiarise people for life with the literature of their civilisation, but also to ingrain the intellectual and spiritual resources with which they could be consoled and guided through life.

Please do comment with your thoughts and recommendations. Which books are missing from the shortlist? And which have you enjoyed most?

The shortlist: forty recommended works of Western literature

Western origins: Ancient Greece

The Iliad by Homer (c. 700 BC)

This is regarded as the first work of Western literature. It depicts the closing weeks of the Trojan War, and the bitter quarrel between King Agamemnon and his finest warrior, Achilles. Like the Odyssey, it is a brilliant, inspiring and fascinating story.The Odyssey by Homer (c. 700 BC)

The Greek warrior Odysseus (also known as Ulysses) returns with his men from the Trojan War to his home in Ithaca. He overcomes monsters and the most brutal elements, only to discover that he must reclaim his homeland and his wife once reaching dry land.History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides (c. 400 BC)

Thucydides was an Athenian general in the great war between Athens and Sparta of the fifth century BC. His account is one of the earliest works of Western history. It is a grand epic, full of wisdom, profound insight and brilliant speeches, including “Pericles' Funeral Oration”.

The Republic by Plato (375 BC)

This is a foundational work of Western philosophy. It explores the nature of the state, government, democracy, justice, and the role of the philosopher and education in society. Plato also examines immortality and the soul. Another landmark work by Plato is his Apology of Socrates, which is an account of Socrates' trial and execution by the Athenian state. Furthermore, the Phaedo is an exploration of the soul and immortality. All of Plato’s works are worth reading.

The Politics by Aristotle (c. 330 BC)

Aristotle was an indispensably important figure in Western thought. Although all that survives of his works are his lecture notes, they are themselves foundational works in the canon. The Politics is a brilliant, and genuinely enjoyable, study of human society. It is, in a sense, in conversation with the arguments of Plato's Republic. Other great works by Aristotle include the Nicomachean Ethics and the Metaphysics.

Ancient RomeThe Aeneid by Virgil (19 BC)

This Latin epic poem narrates Aeneas' journey from Troy to Italy, where he becomes the founding ancestor of the Romans. The Aeneid was for the Romans what the Iliad was for the Greeks: a heroic mythology at the bedrock of their culture.

The Middle AgesConfessions by Saint Augustine of Hippo (400 AD)

As a young man, Saint Augustine led an indulgent life, and was a member of a heretical creed known as Manicheanism. He then underwent a stark conversion to Christianity at the age of 32, going on to become one of the core Church Fathers. His magnum opus was The City of God, which is a critical work of apologetics, describing an enduring conflict between the earthly City of Men and the heavenly City of God. Saint Augustine wrote at the juncture between Antiquity and the Middle Ages; and his works were vitally important to the Christian civilisation that subsequently flourished in Europe after the fall of Rome.

Beowulf by Unknown (c. 975 AD)

The manuscript dates from c. 975, but the myth itself is far older. It is set in a pagan sixth-century Scandinavia. Beowulf, a hero of the Geats, comes to the aid of the King of the Danes to defeat the monster Grendel. It is a fascinating story, with links to Norse and Germanic saga, the Greco-Roman mythic tradition, as well as biblical allusions.

The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (1321 AD)

This epic poem depicts a vision of Dante's journey to the afterlife, through Hell, Purgatory and finally the ascent to Heaven. T. S. Eliot stated that "Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them. There is no third." This is a critical work of world literature.

The Renaissance and Early Modern Period

The Essays of Michel de Montaigne (1533 - 1592 AD)

Montaigne was a crucial figure of the French Renaissance and arguably created the essay as a literary form. He was a significant influence on Shakespeare. His essays made a deep impression on me when I first read them as a teenager. He writes on everything from friendship to war to idleness to the peoples of the New World.

Macbeth by Shakespeare (1606 AD)

I have included only two Shakespeare plays on this list. This is one of Shakespeare’s greatest plays — a tale of ambition, deception, murder and downfall. From the opening pages it is atmospheric, chilling and complex. Shakespeare plays games with language throughout. Like all of Shakespeare's plays, its true meaning subverts modern political sensibilities. Other great Shakespeare plays are Hamlet, King Lear, Julius Caesar, Othello, and the Merchant of Venice. One Shakespeare play, read carefully, is worth ten ordinary books.

Coriolanus by Shakespeare (1608 AD)

This is one of his best, and is also little-known today. It depicts a great general who seeks political power in the Roman Republic. Yet he is banished from Rome by his opponents and pursues vengeance in allegiance with his former military enemies. It is a fascinating exploration of war and the state, military honour, pride, and the nature of democracy.

Paradise Lost by John Milton (1667 AD)

This is Milton's masterpiece. It depicts the temptation of Adam and Eve by Satan, and their exile from the Garden of Eden. It is certainly one of the greatest poems of the English language and was of exceptional importance in the development of theology and culture in Europe.

Great English novelsGulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726 AD)

Swift was a clergyman and an exceptionally influential writer. George Orwell stated that Swift was one of the writers whom he most admired, even though he disagreed with him on every important moral and political issue. This work is a "traveller's tale" through strange lands, which is engrossing, funny and brilliantly written. Moreover, it examines important ideas regarding the individual's relationship to society, the human condition, science, and the sexes.

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818 AD)

This is one of the best novels I have read. A young scientist creates a monster that returns to haunt him. It's an atmospheric adventure story that simultaneously explores the danger of science, and man, unbound. It is also a book that was heavily influenced by major preceding works of the canon.The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg (1824 AD)

Hogg was a Scottish self-educated writer. Initially neglected after publication, this work’s reputation was revitalised during the late twentieth century. The novel depicts Robert Wringham, a Scottish Calvinist, who falls under the influence of a shadowy villain named Gil-Martin. Believing himself to be guaranteed Salvation, he seeks to kill those whom he deems to be damned already by God. It is a fascinating, chilling and complex tale that thoroughly rewards reading. This is a favourite novel of mine.

Barchester Towers by Anthony Trollope (1857 AD)

Trollope is now an undeservedly lesser-read novelist of the nineteenth century. He wrote 47 novels in total and had a formidable writing schedule. His books are widely loved and have drawn an almost cult-like following. In Barchester Towers a bishop dies in the fictional cathedral town of Barchester, leading to a bitter, and also very funny, power-feud.Great Expectations by Charles Dickens (1861 AD)

Dickens was one of the greatest novelists of the nineteenth century. This novel is an excellent place to start. It contains several of Dickens' most famous scenes and characters. He creates warm worlds and arresting portrayals of character and setting. All of Dickens’ works should be read, but other places to begin are The Pickwick Papers and Bleak House. Although I have not included the novelist Thomas Hardy on this list, his terrific novel Jude the Obscure (1895) is a good place to start.The Man Who Would Be King by Rudyard Kipling (1888 AD)

Kipling was a crucial writer of the English canon. His poetry, novels and short stories are exceptional. Yet Kipling, like Conrad, has become deeply unfashionable with the literary and educational establishment due to his treatment of colonialism. In The Man Who Would Be King, two adventurers become kings among Afghan natives. It is a superb tale, which — like much of Kipling's work — functions as a timeless moral parable. I recommend reading Kipling's poetry, which is truly arresting and memorable. His short stories are brilliant also. He captures the vernacular and the outlooks of soldiers brilliantly. His stories reach haunting and highly memorable denouements — for example in Black Jack, which narrates a murderous plot among soldiers.

The White Company by Arthur Conan Doyle (1891 AD)

Conan Doyle is best known for his Sherlock Holmes stories, which are of course excellent. But he believed that his finest works were The White Company and its companion novel Sir Nigel. The "White Company" is a free company of archers in the Hundred Years War, and the novel conveys a young man's journey with the company through Europe and into battle. It is a moving and brilliantly written story that deserves to be much more widely read. So, too, do his non-Holmes short stories. (One of the best that I have read is called The Brazilian Cat.)

The Man Who was Thursday by G. K. Chesterton (1908 AD)

Chesterton was a fascinating and gifted author. Having been an atheist in his youth, he returned to faith and became an important Christian apologist. His writing is lucid and deeply interesting. This novel depicts an undercover policeman who unintentionally becomes elected as an official in a group of anarchist terrorists. It is a raucous and highly perplexing work, on which I have written elsewhere. The novelist Kinglsey Amis used to reread this book every year. Chesterton also wrote the fantastic Father Brown stories and was a powerful essayist.Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell (1949 AD)

This is the ultimate and most important dystopian novel. Like Orwell's Animal Farm, it should be reread continually, for it contains a wealth of insights. Even the geopolitical setting of a world split into three major superpowers has come to pass. His commentary on the abuse of language as a critical tool of power is timeless. This is a work that many pay only lip service to, in my view. It is not simply about Big Brother watching us, but is in fact a large and intricate commentary on the power of the technocratic state to annihilate all freedom in society and the human being. Orwell's social novels are also excellent. I love Coming Up for Air, which is hilarious and as intellectually astute as anything else he wrote.

The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien (1954)

This novel is vastly underrated as an important work of literature. It is not a children's story, but a work that explores power, theology, morality, death, and heroism. I have written elsewhere about how Tolkien reconnects us to Homer and the Western tradition, and defies an age in which it has become fashionable to reject the intellectual and moral heritage of the great books.

Lord of the Flies by William Golding (1954 AD)

This is often portrayed as a children's book. It is in fact a serious and powerful novel about civilisation and the soul of man. Golding's writing is brilliant and gets under the reader’s skin. I would also recommend The Inheritors and his Sea Trilogy. Golding’s work should be read far more widely today.

The Sword of Honour trilogy by Evelyn Waugh (1955 AD)

Waugh was one of the best writers in English of the twentieth century. This trilogy of novels is based broadly on his own experiences of the Second World War. It contains some of the funniest scenes I have read, and is also truly moving. Waugh's writing is brilliantly sharp and clear, and he builds unforgettable characters and scenes. Waugh's other novels, including Put Out More Flags and Scoop, should be read as well.

Master and Commander (the first novel in the Aubrey-Maturin series) by Patrick O’Brian (1969 - 1999 AD)

This series comprises twenty historical novels set largely at sea during the Napoleonic Wars. It is built around the friendship between Captain Jack Aubrey and the ship's surgeon, Stephen Maturin. The series is regarded as a brilliant and important work of literature, and is compared most often to the work of Jane Austen (a major influence on O'Brian). The writing is outstanding, the drama is intense, and the action is thrilling. Perhaps above all, the central characters are deeply compelling. As the British commentator Peter Hitchens (who is exceptionally well-read) put it: "The Patrick O'Brian novels about Captain Jack Aubrey are among the best things written in fiction in the past 50 years, a tremendous epic set in the Napoleonic Wars which is often funny and touching as well as enormously instructive, and so beautifully done that it is a pleasure to read and re-read, and then to read again."

The Great American Novel

Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851 AD)

Melville's epic is the famous story of Ahab's monomaniacal quest to destroy the enormous white sperm whale that bit off his leg on the previous voyage. It is a brilliant, Shakespearean story that thoroughly rewards the investment in time, and contains some of the most memorable scenes of world literature. The great literary critic Harold Bloom described Moby-Dick as a "miracle" of a work. It is profoundly affecting in a myriad of ways: it is hauntingly poetic and beautiful; the characters and motivations are fascinating; and it draws upon the finest traditions of the canon.

European Literature

The Trial by Franz Kafka (1915 AD)

Joseph K. is arrested and prosecuted for a crime that is never revealed. He spends the story suspended in a nightmare of inaccessible bureaucratic angst, constantly striving to understand the accusations made against him. It takes place in a strange, shadowy and cold world. Kafka was an Austrian-Czech civil servant, who wrote several brilliant works that were published posthumously. His novel The Castle finishes mid-sentence, and is an equally fascinating read. His famous story Metamorphosis is about a salesman who wakes up transformed into a giant insect. Although deeply odd, Kafka's works are important, for they express the profound truths about the steady spiritual and moral breakdown of the West, and the darkest aspects of the human condition.

Great Russian works

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866 AD)

This is where to begin with Dostoevsky. It is a fantastic, haunting story about a young man who, drunk on Nietzschean philosophy, murders and robs an old woman. The remainder of the novel traces his feverish spiritual decline as the net of the law tightens around him. It is deeply atmospheric, highly readable, and serves as a timeless moral parable. Dostoevsky was an exceptionally influential writer. He was a socialist revolutionary as a young man, and spent four years in a Siberian prison camp, subsequently renouncing the ideology, and exploring its dangers in his greatest works.

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1879 AD)

This is probably the best novel I have ever read. The great philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein brought this novel to the trenches in the Great War and read it repeatedly. The plot centres around four brothers and the apparent patricide of their father. The first half builds slowly (as most of Dostoevsky's books do), and the second is truly thrilling and fascinating. Throughout, Dostoevsky examines faith, doubt, nihilism, God, reason, and man's final purpose. It also contains the brilliant and famous story of “The Grand Inquisitor”. I cannot recommend this one highly enough.

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1869 AD)

This famously long work is certainly one of the greatest works of world literature. It describes the lives of Russian aristocratic families during Napoleon's invasion of Russia. It moves between great battle scenes, the ballrooms of high Tsarist society, the command tents of Napoleon and the Russian generals, and long evaluations on history and philosophy. It is a brilliant work and well worth the time.

The Heart of a Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov (1925 AD)

This short and brilliant novel can be read in a single day. A professor transplants a human pituitary gland into a stray dog that he has taken in. The dog, now half-man and half-beast, comes to tyrannise his owner. This is a scathing satire of the Bolshevik Revolution, and one of my favourite books. Bulgakov’s Master and Margherita and The White Guard are exceptional also.

Great English essays

The Major Works of Samuel Johnson (1730 - 1784 AD)

Samuel Johnson, also known as Dr Johnson, was perhaps the greatest man of letters in the English language. With a formidable intellect and good moral sense, he was an exceptional essayist, poet, playwright and critic. I recommend The Major Works of Samuel Johnson, published by Oxford Classics. Like all outstanding writers, he was polymathic and wrote on a vast array of topics — from capital punishment to marriage to Scotland to the pleasures of drinking tea. His fifty-page essay on Shakespeare is truly inspiring; whilst his poetry and diary entries are profound and often deeply moving. James Boswell, a friend and acolyte of Johnson, wrote his Life of Samuel Johnson, which is itself an important and popular work of literature.

Essays by George Orwell (1925 - 1950)

Orwell's brilliant essays are an outstanding example of how to write with exceptional clarity, purpose and skill. Like Johnson, it seems that nothing is outside of his remit. He writes on science, toads, war, nationalism, socialism, homelessness, and shooting an elephant. One feels personally addressed when reading Orwell. In these essays we see the extremely vigorous intellect and unflinching honesty that created the great works of fiction for which he is known. Like other great authors on this list (Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, for example), Orwell was a man of the world - he was wounded in battle during the Spanish Civil War and had lived in dire poverty in London and Paris. I have written at length on the power of these essays.

European and Military history. "War is the father and king of all: some he has made gods, and some men; some slaves and some free." — Heraclitus

The Guns of August by Barbara Tuchman (1962 AD)

This is a brilliant work of history centring on the opening months of the First World War. It is a fascinating account of the conflict's geostrategic pretext and the grand manoeuvres that led to the great powers being sucked into terrible, stalemated fighting that almost no one foresaw. It is written in lucid prose, and gives one a birds-eye view of the generals' map-tables. John F. Kennedy gave copies of this book to his staff during the Cold War to educate them on the dangers of hubris and miscalculation. This book deserves to be read and re-read widely.

Goodbye to All That by Robert Graves (1929 AD)

Graves' brilliant memoir of his early life and service as an infantry officer in the Great War is exceptional. The writing is excellent, and the account of trench service is both fascinating and brutal. This book should be read in schools as an education on the social history of Britain and the sheer scale of the sacrifice endured by all of Europe in the Great War. Graves also wrote I, Claudius, a novel set in Ancient Rome. In addition, he authored a detailed account of Greek mythology.

The Judgment of the Nations by Christopher Dawson (1942 AD)

This short work of history deserves to be far better know. Dawson was a highly influential historian of the twentieth century. Here Dawson describes the breakdown of Europe that led to the Nazi project. He focuses on the theological and intellectual degeneration that took place after the Reformation, particularly in Central Europe. It is a slightly difficult read, but is well worth the effort, since it illuminates the true historical and religious origins of the modern world. Dawson also wrote the excellent Religion and the Rise of Western Culture, which details the immense spiritual and cultural regeneration that took place during the so-called Dark Ages after the fall of Rome.

The End of Everything by Victor Davis Hanson (2024 AD)

Although very recent, this work of history will be read for years to come. Hanson is an important classicist and military historian. Here he describes the annihilation of four previous civilisations: Thebes; Carthage; Constantinople; and the Aztecs. It is fascinating throughout. Not only does it give detailed insight into major chapters of history, but it also reveals the critical lessons about civilisational strength and military power that are so relevant to us today.

Apologetics. Christianity is at the bedrock of our civilisation and of the Western canon. I have therefore recommended two works that make the case for the truth of Christianity. Furthermore, the major apologetics by Saint Augustine and Saint Thomas Aquinas, for example, are important works of literature in their own rights.

Mere Christianity by C. S. Lewis (1952 AD)

Lewis turned away from Christianity during the Great War. But his friend, J. R. R. Tolkien, who had also served as an infantry officer, convinced him to return to faith. This short book gives a series of compelling arguments for why, in Lewis' view, God must lie at the basis of the material world. It is a very popular book and is well worth the time to read closely, not least of all because it was written by a man who had only recently been overcome with doubt. I also strongly recommend Surprised by Joy, which a biographical account of the same theme.

The Last Superstition: A Refutation of the New Atheism by Edward Feser (2010 AD)

Feser is a Catholic academic philosopher. This book is a direct challenge to the New Atheism of Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens et al, and has been highly influential. Feser takes the reader on an expert journey through the traditional metaphysical arguments for God's existence, revealing that they are in fact far, far more compelling than students have been led to believe in recent decades. Indeed, every major philosopher from Socrates until the modern age held that, logically, God must lie at the base of the world. Feser demonstrates that the New Atheists simply do not understand the depth and strength of the philosophical arguments for God's existence, and that their project is built on an unjustified and, frankly, ignorant hubris that is not shared by the finest secular philosophers like Thomas Nagel. Although technically difficult in places, Feser has deliberately written this book for the layman. Whatever one's religious persuasion, it is an intellectually formidable, well-written and fascinating defence of our civilisation's central religion. I recommend moving onto his more demanding Five Proofs of the Existence of God. (In addition, Peter Hitchens' The Rage Against God is an excellent, short and highly accessible argument in a similar vein.)

Thank you for the list. Well done. #1 on your list is the most vital of course. Very happy to see Tolkein, Dawson, Lewis, Feser et al on this list. Happy reading!

These days the world is opening up from the dark ages of Christendom, a world dominated by colonialism, superstition and arrogance, that was notable for it's gross disrespect of other cultures, so I think we should also add a few classics of Japanese, Indian, Latin American, Chinese and African literature - secular and religious, many of which are as distinguished and ancient as our own.

But if we MUST focus on Western literature, then this list is notable for its deficiencies, and Geoffrey Chaucer's 'Canterbury Tales' merits more than a mention in passing.