Why the intellectual elite is always wrong

The culture is now a chaotic tyranny of vacuous "takes"

Political discourse has been reduced to an endless battle of “takes”. Miniature critiques of every newsworthy matter are churned out constantly by the so-called intelligentsia1. Most such takes are expressed in under three sentences on Twitter by ostensibly serious people who possess only the shallowest understanding of the subject at hand.

It has created the impression of visceral disputation — a perpetual war of culture and ideas. But this is an illusion. Beneath it lies an immense chasm of braindead thought that is at once tediously superficial and dangerously conformist. The luminaries of the mainstream intellectual elite do not really know what to think about anything; and they agree on basically everything. There is no true conviction of opinion, except in regard to those dogmas which are enforced within the narrow parameters of compulsory orthodoxy. Even for the most forthright of touted idealogues, their worldview can be boiled down to a handful of vapid received shibboleths.

It has been this way since the advent of the Enlightenment. David Hume, the Scottish philosopher of the eighteenth century, remarked on the new tedious hypercriticism of his own day:

“There is nothing which is not the subject of debate, and in which men of learning are not of contrary opinions. The most trivial question escapes not our controversy, and in the most momentous we are not able to give any certain decision. Disputes are multiplied, as if everything was uncertain; and these disputes are managed with the greatest warmth, as if everything was certain.”

The culture of specious “criticism”, like the Enlightenment itself, emerged from the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. With Catholic theology under continuous assault from Protestantism, an exalted struggle to rebuild Western thought on new rational principles was born. A blank page stood before the forces of progressivism on which everything could be rewritten: man’s relationship to God and nature; economic relations; monarchical power; and the very cultural fabric of civilisation.

“Modernity has attempted to replace metaphysics with politics. Politics has been stretched to encompass, in a meaningless and superficial way, the great eternal questions of ethics and existence.”

But in this Brave New World of possibility, a strange unparalleled conformism emerged. Most elites have since cleaved to accepted critiques that take as their centrepiece the abstracted ideals of rational progress. Yet the core precepts of these doctrines have persistently been downright wrong.

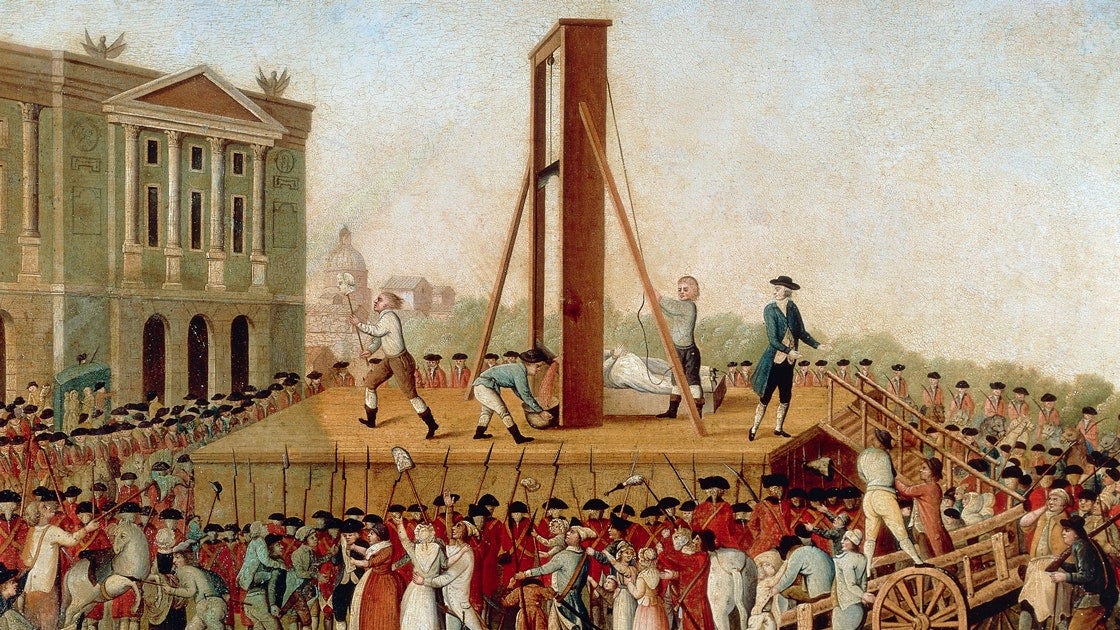

Indeed, we can trace the gross errors of the intellectual elite back centuries. In 1789, the French Revolution was regarded by the British intelligentsia as an important waypoint in the inexorable rise of liberty and enlightenment. The philosopher Richard Price, drawing a then-commonplace comparison with England’s own Glorious Revolution of 1688, declared in November 1789:

“Behold all ye friends of freedom...behold the light you have struck out, after setting America free, reflected to France and there kindled into a blaze that lays despotism in ashes and warms and illuminates Europe. I see the ardour for liberty catching and spreading; ...the dominion of kings changed for the dominion of laws, and the dominion of priests giving way to the dominion of reason and conscience.”

However, it was through the dissident intellectual force of Edmund Burke that critique of the Revolution found its greatest and truest expression. Long before the rise of Napoleon, Burke prophesied that a popular general would emerge as “master of [the French] assembly, the master of [the] whole republic.” Against the optimism of the intelligentsia, he saw that a society based upon abstracted political precepts, rather than tradition and the realities of the “human heart”, would lead inevitably to chaos and tyranny.

It was specifically in the abstractions of “liberty” and the “rights of man” that Burke identified new and potent sources of human oppression. Thus, having drawn the ire of the establishment for breaking with Enlightenment orthodoxies, Burke’s popularity in the House of Commons waned. Yet he was vindicated unambiguously: the French Revolution disintegrated into a nightmare of regicide, terror, atheistic persecution, and military dictatorship.

In the twentieth century, too, the intelligentsia was beholden to maddened dogma. In 1917, Lord Lansdowne published a letter in The Daily Telegraph attacking the immeasurable civilisational harm of the Western Front. He called for a peace settlement with Germany to restore the ante bellum status quo. He wrote: “Those who look forward to the prolongation of the war… [differ] only in the degree from that of the criminals who provoked it.”

He impressed Woodrow Wilson with cogent arguments for returning Europe to peace on enduring first principles. Yet he was rounded upon with astonishing aggression by the British Cabinet and press. In the fever of war, a destructive zeitgeist of death and sacrifice and perseverance had been forged. Meanwhile, Lansdowne received mailbags full of supportive letters from the public.

However, having suffered so deeply from the folly of that war, the British elite then formed a set of senseless appeasement orthodoxies in the 1930s. These were challenged by another great prophet of catastrophe: Winston Churchill. In his “Wilderness Years” on the backbenches, he rose repeatedly in the Commons to warn of Germany’s inexorable expansion. He was dismissed as a “warmonger” until it was too late.

We might contrast this with the neo-conservative — neo-liberal, in fact — aggression against the sceptics of the Iraq War. Those opposing rash utopian interventionism were smeared as Baathist “sympathisers”. Within months, the critics’ warnings had been realised with horrible clarity. It is estimated that around one million people had died as a result of the war by 2008. The true toll can never be known. Importantly, the full extent of the harm inflicted has never been acknowledged.

And as we stumble ever-nearer to a potentially nuclear climax in Ukraine, the sceptics of further Western aggravation in the conflict have been suppressed by an overwhelming and hysterical new orthodoxy.

Thus, we see that elite opinion oscillates between the hysteria for war and the irrational pursuit of peace, the advocacy of bloodthirsty revolution, and the unwavering support for tyranny. The blind wrongness of elitist dogma was perhaps captured most brilliantly by the great conservative writer Macolm Muggeridge, who wrote of the pro-Stalinist orthodoxies of the 1940s:

“…a murderous Georgian brigand in the Kremlin acclaimed by the intellectual elite as wiser than Solomon, more enlightened than Ashoka, more humane than Marcus Aurelius.”

This notion of phoney enlightenment is the key to the elitist mentality. It is that which underpins the power of the dogma and the lies — the conviction that their beliefs are on the side of unquestionable rational and moral progress. The moment of Now is the strongest political force. And hence dissenters are regarded as neo-heretics — defectors from liberalism, which is Modernity’s binding moral doctrine.

Why has this happened to our culture? Ultimately, in the absence of great metaphysical ideas — the so-called death of God — the human spirit has been captured by the domain of politics. The most profound mysteries, as Hume noted, lie unanswered and barely considered. Yet delusive political propaganda is advanced with absolute certitude by a powerful class of hubristic and dogmatic cultists.

This is no accident. Modernity has attempted to replace metaphysics with politics. Politics has been stretched to encompass, in a meaningless and superficial way, the great eternal questions of ethics and existence. Even science, like the arts, is now beholden to political dogma. Richard Price’s utopian aspiration of 1789 is fulfilled: religion has been replaced with a “dominion of reason”. The result is a rotten, lie-ridden culture.

Thus, behind the constant drone of shallow, wrongheaded critique lies no light at all — only chaos and an ever-growing nemesis of power-lust, totalitarian conformism, and darkness.

The class of prominent politicians, journalists, academics and cultural figures that comprise the establishment.